I can remember at least three pivotal moments where my life’s path faced a fork and I had to choose between the known and the unknown. The first was when I chose to remain at my high school in Queens despite being accepted to Stuyvesant High School in Manhattan, the second was when I opted to not study abroad in Paris during college, and the third was when I decided to return to Boston for my post-baccalaureate premedical studies at Harvard instead of attending UC Berkeley. Each time, I presumed that the advantages of the familiar outweighed the disadvantages (which in retrospect turned out to be overblown), and while I am happy about who I have become and grateful for the people and opportunities and experiences in the journey I have lived, I sometimes wonder who I might have been had I gone the other way.

Write to Understand

Thinking about my choices leading up to medical school, I decided that I needed a different philosophy if I hoped to satisfy my cravings to grow and change. It helped that my time in medical school already began as an uncertain journey. I was a coastal, city kid who had been accepted to only a single medical school that believed in me, a historically black institution, Meharry Medical College in Nashville, TN. I was unsure what type of culture shock living in the South would bring. But my worries soon abated after I met two classmates, Michael and Ellis, who also regarded medical school — its challenges, culture, and competitiveness — with wariness.

Early on the three of us found kinship in grabbing pizza, shooting pool, and playing racquetball. We sat at the same table in our favorite sushi spot once a week, holding deep, philosophical conversations covering everything between the meaning of reality to medical ethics to why we would never give up the humanities. We were each roughly five years apart, allowing us to evaluate our similar predicaments from three different perspectives. As a way to help us process the different experiences and the new start to our lives, I proposed that we write a journal entry once a week and then meet to read them aloud to each other.

For the next twelve weeks, we met and shared our short essays, finding catharsis in our private therapy sessions. To amuse ourselves, we called our meetings “The Writing Club,” and with a name came some attention. A classmate even emailed us a sample of her writing as an application to join the club, which caused us to briefly, hilariously, consider disbanding because her writing surpassed ours and we felt that she would only see us as amateurs. Ultimately, we neither expanded nor disbanded, but instead stayed with our writing club long enough for it to transform into something special.

Don’t Pass Up An Intriguing Opportunity

One day, waiting for lecture to start, one of our classmates approached us in the back corner of the lecture hall where we usually clustered. She was a delegate for the African Student Union (ASU), a campus group, and she wanted to know if as (ahem) writers, we would be interested in writing and directing the play for the group’s annual fundraiser. Without hesitation or a doubt in my mind, I agreed. My friends thought I was crazy but they were still game for anything.

I found the idea intriguing which is why I felt compelled to go for it, but I was also not totally devoid of experience. In high school I wrote comedic skits and acted in plays like Hamlet and Macbeth. In my freshman year of college, I tried out unsuccessfully for improv comedy groups and acted as Paris in Romeo and Juliet. I had even taken a sketch comedy writing class at a comedy club one summer in New York. But after that, my involvement in theater, comedy, and acting waned as my interests in other aspects of college life grew.

But what I had never done was take on the responsibility of a project of this scale for a live audience, working without a specific plan, with people who did not know me, and in a place totally foreign. Usually, I participated as a small part in someone else’s vision. I focused on my small role, my lines, my cues, and my costume. I did not pay attention to anything outside of that. But now, this was a chance to influence the entire production on a different scale. Michael, Ellis, and I found the prospect thrilling.

Nothing Worthwhile Comes Easy — Be Ready to Grind

Over the next few months, my friends and I worked on writing the script. We wanted one that would tell a story, teach a lesson, get some laughs, and finish with a happy ending — a pretty easy task, right? The theme of the fundraiser was East versus West, so we started with research. We read about African cultures and storytelling, we accepted continuous feedback and suggestions from the members of the ASU, and we blended it together with our own experiences as Millennials in medical school.

Our play followed a classic story pattern: children-are-in-love-but-parents-disapprove. But rather than make it about the lovers, we decided to focus on the parents, especially the relationship between the fathers. Each of the families represented East and West Africa. The desire parents often have for their children to marry within their cultures would be the driving force to generate conflict.

One major challenge we faced was casting, which was not an easy feat when all the actors were busy and stressed out medical students. We ended up recruiting actors mainly from our class, which, in retrospect, seemed risky for first-year medical students to be spending their limited study time acting in a play. Michael organized the music and sound effects, Ellis mastered the lighting, and others friends gathered props and costumes. All the while, we continued to hone the script to fit our actors, our space, and our time.

Even more than the main event, rehearsals have always been my favorite part of any production. This is when the troubleshooting, reorganizing, discussions, and creativity happen. All of a sudden we would realize that a scene requires a prop or we need to rework the timing of an entry or certain physical actions must be choreographed. The entire cast and crew would offer solutions and multiple versions of an idea would be attempted. It was an intoxicating collaborative environment. For two weeks leading up to the show, we held rehearsals after long days of classes, which despite being exhausting, taught me the most about how to lead a team through problems and how to effectively improvise solutions.

We faced many internal obstacles as well. Early on, I remember our work being criticized by a few members of the ASU leadership team, which lessened as our vision became clearer. I also recall, with embarrassment, losing my temper when something did not go according to plan, which caused me immediate regret. But the project was moving forward and we were getting better with each rehearsal, so, at the time, I assumed the ends justified the means. My continued evolution since then have taught me that this is rarely the case and better solutions are possible.

After months of rehearsals and hard work, we were finally ready for our big night. While no recording exists (which is perhaps why I am memorializing it with this essay), I remember our actors nailing their lines and knocking out their performances. As expected, the lights and sounds were on cue. The audience of some 200 people seemed riveted and reacted how we wanted at all the right moments. While watching the play from the small control room at the back of auditorium, a sense of accomplishment passed through me. I started to finally believe in myself. There was not a project too big that could not be executed as long as there was a proper plan.

Deconstruct a Project to its Smallest Components

My confidence in my creative abilities grew and this endeavor led me to launch a string of projects over the years that have improved how I learn, create, and communicate. Now I am less likely to write off an idea and more willing to evaluate if I have the appropriate resources — time, energy, motivation, and capital — to execute it. Additionally, I find myself actively seeking novel opportunities, which is how I was able to invent a curriculum and teach a college course in my last year of residency.

My projects solved the problems that I was facing, while also fulfilling my deep desire to make something. I did not always have a plan when agreeing to a task. Most of the time, I had no experience. But I felt comfortable with the ability to teach myself, felt emboldened that I was getting the chance to take a risk, and had a general initial approach to problem solving.

Different parts of software, if designed and written efficiently, separate tasks while also reducing repetitiveness. This allows software developers to wield maximum control over their code, allowing them to change specific variables in the program to test different conditions without crashing the entire system. They generally accomplish this by starting with a high level concept and then progressively breaking it down to individual components and then into even smaller problems and then singular tasks. This way they are able to identify every specific part of their application, how they want it to function, and then build it from the bottom.

In a similar way, I started with the high level of the play and then broke it down to as many large categories as I could:

- Script

- Props

- Lighting

- Costumes

- Marketing

- Rehearsals

- Actors

Then I thought about what I wanted to accomplish out of each of the categories and then reduced them into even smaller groupings:

- Marketing —> flyers, emails, word-of-mouth, etc.

- Rehearsals —> time, location, participants, announcement, etc.

- Props —> which act? which scene? storage, owner, etc.

I continued the process until I felt like I had reached the smallest unit of work to get forward progress:

- Flyers —> Design, Make, Get Feedback, Revise, Print, Post

This produced a list of tasks that I could follow systematically, giving me certainty in advancement and steady dopamine boluses each time I checked off an item.

How Many Chance Do You Have Left?

Despite having a long history of participating in small and large projects, being part of teams, even holding leadership positions, the understanding of what it took to execute on larger complex projects eluded me. But for once, rather than using that as an excuse to not try, I allowed myself to embrace my own inexperience and seize the moment instead. When faced with similar situations, now I ask myself, “How many more times in your life will someone let you try this?”

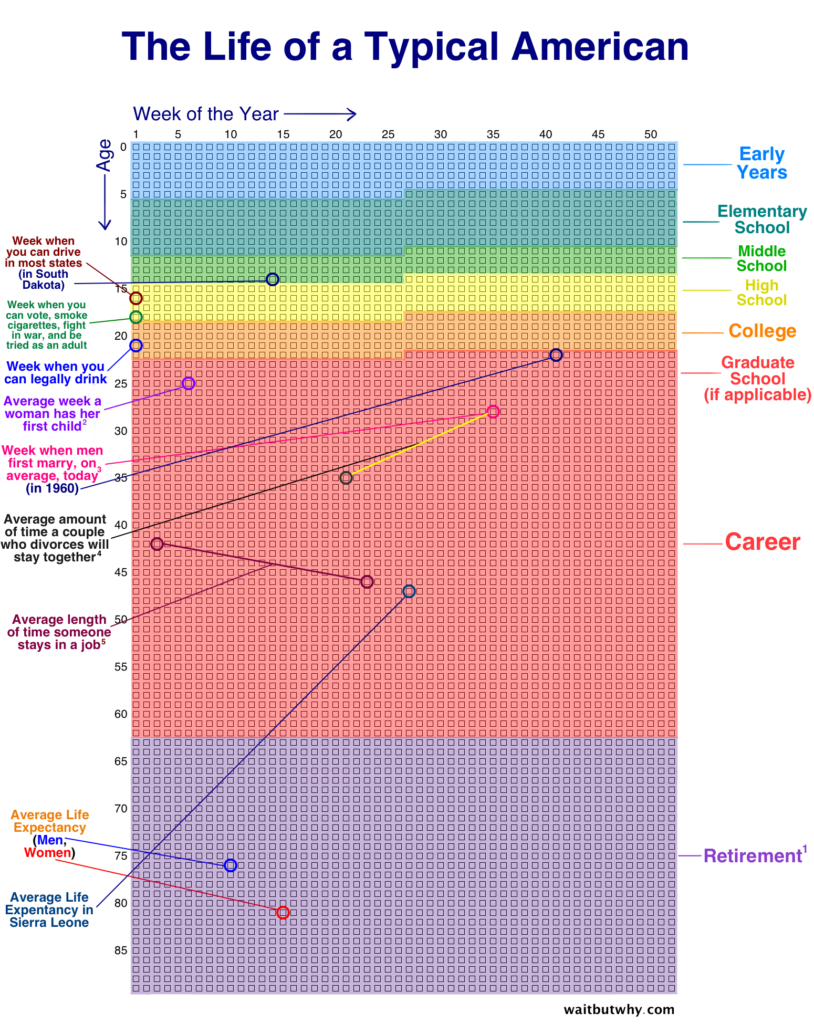

In an essay for the blog, Wait but Why, Tim Urban creates a chart that demonstrates what a 90 year life looks like in weeks. He uses it to make the point that while some parts of your life seem fast and some move slow, it is most certainly finite. The number of weeks or opportunities we have left in our lives to accomplish all of our bucket list items are a lot less than we realize, especially when you take into account that we will not all make it to 90 and the length of our healthspans will be even shorter. So when offered a chance to do something unique or with a worthwhile payoff, it is in our best interest to go for it whether we have a plan or not. At the very least, we should give it real consideration.

Another reason to not pass up on creative projects or opportunities is that we never know what new talent we might discover or what new skills we might be able to carry over to a different part of our lives. For example, after studying the principles of graphic and user interface design when developing an app, the design of my powerpoint presentations improved dramatically. One of the reasons I challenge myself to write as often as I can is because I recognize that these are the reps I need to write a book one day.

They say that luck is when preparation meets opportunity, but to gain the full benefit, it is best that opportunity and preparation are actively sought. As long as you are not overextending yourself (wellness still matters!), challenge yourself to step outside your comfort zone. Give yourself a chance to create and learn from projects that succeed and fail. It is okay to figure it out as you go. When you stop to think about it, that is all any of us are doing in life. None of us have ever been the age we are now or living in the exact moment we are now. This is the moment when we can define ourselves. Otherwise, if we don’t take the uncertain path or the road less traveled, then we might catch ourselves wondering, later in time, who that other person might have been.

Thank you for reading.

Interested in learning more? You can support me by:

- Purchasing Hamlet, Macbeth, or Romeo and Juliet

- Reading my prior work “Why Historically Black Medical Colleges and Universities Matter” or “Your Existence: The Definition of Improbable”

- Keeping up with my work on Instagram or Twitter

- Signing up for my mailing list below (on mobile) or the right side bar (on desktop)