Imagine this. You are the conductor of a train hurtling along at rapid speed. You are trying to make up for lost time and for some reason the radio is not working so you don’t have contact with your destination. It’s hot and humid and the horizon appears hazy. Squinting into the mirage, you get a feeling in the pit of your stomach that something isn’t right.

As the train moves forward, it becomes clearer why you feel sick. Up ahead the train track forks in two directions. On the set of tracks that you are traveling there are five workers repairing the rail. On the other track is a single worker. Unfortunately, they seem oblivious to your approach. You try to pull the brakes but they are jammed. You try to blow the horn but it doesn’t work either. The only thing you can do is pull a lever that will divert the train from the track it is currently on to the track with the single worker.

What do you do? You can choose to do nothing and let the train run over the five. Or you can pull the lever and sacrifice the one. Do you pull the lever?

This is known as the Trolley Problem, which was conceived by the philosopher, Philippa Ruth Foot in 1967, and later expanded upon by the philosopher, Judith Jarvis Thomson in 1976. It is one of the most famous thought experiments in the field of ethical and moral philosophy.[1]Consider morals as referring to guiding principles and ethics as specific rules, actions, or behaviors. It forces us to ask questions like what it means to have choice, what is the responsibility we have towards others, and can one life be traded for another (or five).

For many people, the choice is simple. They would pull the lever. After all, one death is not as bad as five, right? But there are other bizarre variations of The Trolley Problem that make it a fascinating exercise. What if the single worker on the track was your child? Would you still pull the lever?

Or what if instead of being the driver of the train, you are instead a bystander standing on a bridge above the tracks. Below you are five workers on the track, unaware of an oncoming train. Standing next to you is a large man, peering over the ledge. Presumably his mass is great enough to stop the train and spare the five lives. What do you do now? Should you push him?

And if that seems to be far-fetched, consider this variation. What if there was a young and healthy prisoner, who is serving a lifetime sentence for a mass shooting that led to the loss of dozens of lives. In the same state, there are five upstanding citizens; each is suffering from the failure of a single organ: a kidney, a liver, a heart, a lung, and a pancreas. It turns out they happen to be close immunological matches with the prisoner. Is it justified to kill the prisoner and transplant his organs to the five who need them?

The Joy of Philosophy

Philosophy has always fascinated me. Growing up I rebelled against my parents’ religion because the answers I was given to the existential questions of why we are here or what is our purpose or who I am did not satisfy me. But it was not until college, when I realized my affinity for community service and social justice, that I began to seriously think about questions like what does it mean to be a good person, what is right and wrong, and how do we live a “Good” life.

I ended up taking two courses called The Challenge of Justice and The Challenge of Peace that introduced me to the many schools of moral philosophy like Aristotle’s virtue ethics, John Stuart Mill’s utilitarianism, Immanuel Kant’s categorical imperative, and Catholic social teaching (I attended Boston College, a Jesuit university). The class also explored modern philosophers of justice like Martin Luther King, Mahatma Gandhi, Malcolm X, Desmond Tutu, Peter Singer, and John Rawls. They were my favorite courses in college and, throughout the years, whenever I encountered a new philosophy, I have had a useful point of reference to compare these ideas to those I had been familiar with in the past.

How to Be Perfect

But like all things, knowledge fades the less you engage with it. So it was a pleasant surprise when a great friend[2]As far as I am concerned, a friend automatically becomes great when he or she shares a book on how to be a better person. The fact that they were seeking their own moral self improvement is reason … Continue reading of mine recommended the book How to Be Perfect by Michael Schur. He is a television producer, writer, actor, and director. He was a writer for Saturday Night Live and The Office, co-created Parks and Recreation, produced Master of None, and, relevant to this conversation, created The Good Place. It is his interest in moral philosophy that led him to create the show and he continued his exploration by writing this book.

As you might have guessed, Schur is a comedy writer and it is on full display in the book, which ultimately turns out to be an excellent introductory (or refresher) manual on moral philosophy. Amidst the funny footnotes, whimsical musings, outlandish thought experiments, Schur considers what it means to be a good person, how knowledge of different philosophies might help us make better decisions when faced with ethical quandaries (although he steers clear of the religious ones), the importance of recognizing our responsibility to other people, why we should be aware of our personal shortcomings — especially the inevitability that we will make mistakes and hurt people — and, despite that, why we should continue to strive to be better people.

It’s an uplifting book (definitely the type of book worth gifting) and something that I will certainly revisit. Since I believe in the importance of writing to learn, I can’t pass up the chance to summarize my favorite ideas in the book. Hopefully, it will spark your interest and you can do your own deep dive into moral philosophy.

As you read through these ideas, keep in mind that philosophy is often based in thought experiments that are impossible to execute in real life. But do not let that detract from the argument or deter you. Instead look at these ideas as a set of tools you can use to evaluate moral conundrums in your life and give you a better idea on how to safely and ethically proceed.

Aristotle, Virtue Ethics, and the Golden Mean

Aristotle lived in Greece in the 4th Century BC and, along with Plato (who was his teacher), is one of the godfathers of Western philosophy. He was a polymath who wrote about a range of subjects like physics, biology, aesthetics, metaphysics, poetry, music, psychology, economics, politics, and more. When it comes to ethics, Aristotle wrote in his book, Nicomachean Ethics, that a person’s telos (Greek for goal), which is similar to one’s raison d’etre or purpose, is eudaimonia, which can be translated as “happiness,” “flourishing,” or “well-being.”

In order to reach this state of eudaimonia, a person must obtain the right amount of virtues, which are qualities that make us good humans. Virtue ethics is based on Aristotle’s belief that everyone’s being and personality exists on multiple spectrums of virtues. And the aim for each one of us is to find the perfect balance on the spectrum. Further he elucidated that no one is born perfectly virtuous, to obtain these virtues we must do virtuous things, and the pursuit of eudaimonia is a life long process. It is only with practice and repeated failing in the pursuit of a virtuous temperament can we achieve happiness.

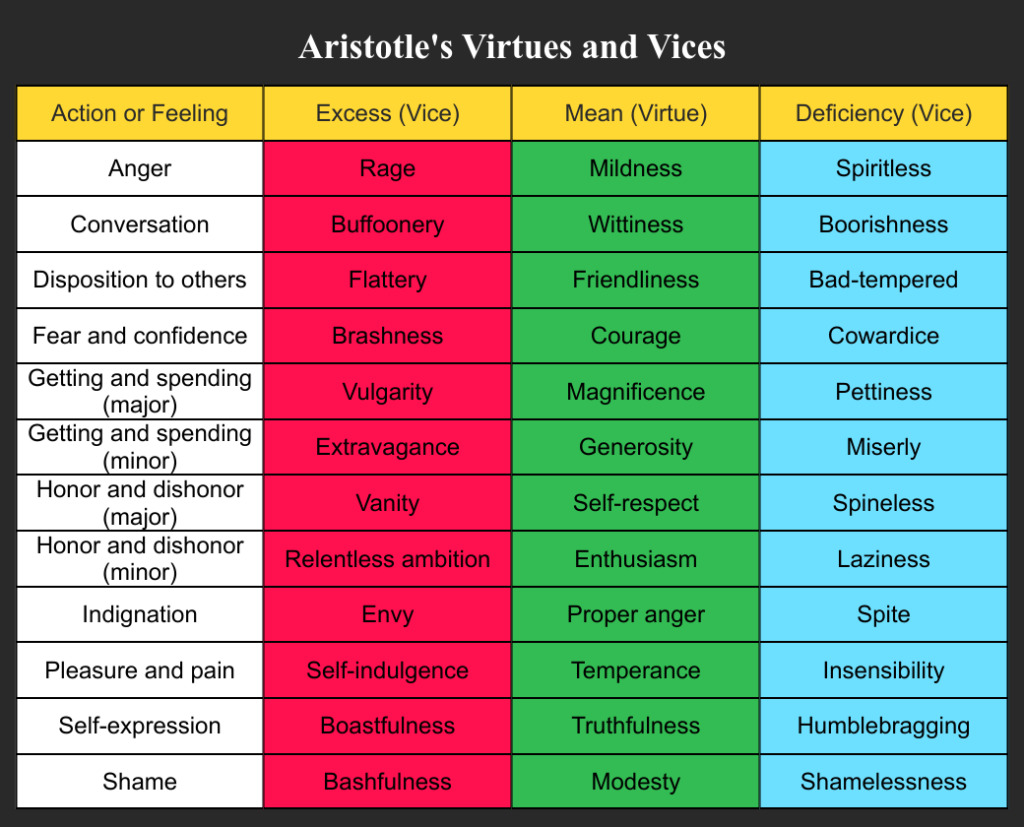

The ideal location between an excess and a deficiency of a virtue is known as the golden mean. This is where we want to be forever calibrating ourselves in order to flourish. For example, on the spectrum of anger, from being spiritless to having rage, the golden mean is to have an even temperament. Essentially, not too much or too little anger. Occasionally there will be situations that require us to be more or less angry. This is okay, as long as we only demonstrate the amount necessary or proportional to the context of the action. If someone hurts your family member, it is okay to be enraged. But don’t show that same fury when someone cuts you in line at Starbucks.

Aristotle listed 12 virtues but you can probably think of many more:

John Stuart Mill, Jeremy Bentham, and Utilitarianism

Two of the most famous philosophers in the school of Utilitarianism were 19th century British men: John Stuart Mill and, his student, Jeremy Bentham. They championed a philosophy which seeks to find the action that derives the maximum amount of happiness for the most amount of people, which Bentham dubbed “the greatest happiness principle.” It is from a branch of philosophy called “consequentialism,” which is focused on the results or consequences of our actions. Regardless of how a result is obtained, it is the total amount of happiness derived at the end that matters.

This is the moral philosophy that is most immediately useful in the trolley problem above. When trying to decide whether or not to pull the lever, you might find yourself weighing the happiness derived from saving five lives versus sparing one. However, while the greatest happiness principle might be one of the easiest to understand and apply in simple cases, it is also one of the easiest to argue against. How do you measure the amount of pleasure or pain an action causes? How often are you certain that one action is a direct consequence of another? And if a town of religious zealots collectively decided to burn a few women at the stake [or insert another marginalized community here] because of their belief that they are witches, does the collective happiness they derive at the expense of the falsely accused morally justified?

Immanuel Kant and the Categorical Imperative

For a long time, Immanuel Kant was one of my favorites. He was an 18th century German who endorsed deontology, which is the study of duties and obligations. Kant believed that we should derive our morality from pure reason and then establish certain maxims that we can adhere to. As a contrast to utilitarianism, Kant focused more on our reasons for acting a certain way and our duty to be consistent in that behavior, regardless of the consequences. It is the principle of the action that ultimately matters.

In his book, Foundations of the Metaphysics of Morals, Kant describes the categorical imperative, which is to

“Act only in accordance with that maxim through which you can at the same time will that it become a universal law.”

This can be understood through the following formula. When faced with a morally questionable action, you should:

- Establish a maxim or rule that explains your potential action. Then ask yourself:

- What if this was a universal law of nature that all rational agents followed in similar circumstances?

- Could there even be a world with this maxim as a universal law of nature?

- Would or could you rationally act on this maxim in that world?

If you are able to get through all four steps, then your action is morally permissible.

There is another version of the categorical imperative called the practical imperative, which declares that we should

“Act so that you treat humanity, whether in your own person or in that of another, always as an end and never as a means only.”

This is the rule that I appreciate the most about Kant. Of course we use people all the time for their talents, wisdom, and abilities. However, Kant is warning that us that we don’t use people merely or only as a means, but we must respect their humanity as well.

T. M. Scanlon and Contractualism

T.M. Scanlon is a Harvard professor, who wrote the book What We Owe Each Other and was one of the principle influences for Michael Schur when he was writing and creating The Good Place. Scanlon’s claim to fame is contractualism, which is explained with a thought experiment that assumes an agreement where all members of a society attempt to establish and agree to a reasonable set of rules or guidelines on how to live and how to treat each other. Ideally, in this hypothetical negotiation, all sides temper their own desires and interests in order to accommodate each other’s needs and try to find some sort of harmony amongst the differences.

There is a particular emphasis on being reasonable. If I object to a rule because it negatively affects me, but every other proposed rule negatively affects other people more, than by being reasonable, I should withdraw my objection. Does this remind you of masking up during the pandemic, anyone?

There are two important things to note. First, Scanlon does not see this as an abstract exercise in rationality on how to act like Kant’s categorical imperative. Instead, the guidelines must be decided with other people. We must consider the feelings of everyone and do this together. Second, all people and their needs are seen as equals and anyone can veto another’s proposed rules if they are unjustifiable and unreasonable.

Where contractualism might fall short is that in searching for a common ground with all people, we find ourselves at the least common denominator. In an attempt to appease everyone, contractualism might become extremely diluted, only getting us to a baseline level of morality.

William James and Pragmatism

William James was another Harvard philosopher and historian in the late 19th century. He was the first professor to offer a course on psychology in the United States, earning the unofficial title of the “Father of American psychology.” His contribution to philosophy is an idea known as pragmatism, which is concerned with living by empirical or experienced and practical truth rather than theories or principles.

In other words, pragmatism seeks to use whatever philosophical, psychological, or scientific tool available to get to truth or practicality. It is less concerned with which philosophy or religion or dogma can give us guiding principles, but which ones leads to the proper, practical result. In some cases the answer might be utilitarianism and in others we might need to turn to Buddhism or the categorical imperative or contractualism. Essentially this was conceived “so that metaphysical disputes that appear irresoluble will be dissolved.” For example, in the debate about free will versus determinism or the existence or non-existence of God, since we cannot prove either side, does it really matter, practically speaking? Believe what is best for you as long as your actions are ethical.

Ayn Rand and Objectivism

The contrarian in the group is Ayn Rand, who was a 20th century writer and philosopher most famous for her theory of Objectivism, which she expounds upon in her best-selling books Atlas Shrugged and The Fountainhead. She advocated rational and ethical egoism, claiming that not only should we act in our own self interest but that it is rational to do so. Further, she explicitly rejected altruism, which she equated to self-sacrifice, self-immolation, and self-destruction for the sake of others.

Rand described Objectivism as

“the concept of man as a heroic being, with his own happiness as the moral purpose of his life, with productive achievement as his noblest activity, and reason as his own absolute.”

Her Objectivist virtues include rationality, honesty, justice, independence, integrity, productiveness, and pride. It should be of no surprise, then, that some of her major adherents tend to be libertarians, right-wing conservatives, Wall Street financiers, and Silicon Valley entrepreneurs.

Susan Wolf and the Moral Saint

The contemporary philosopher, Susan Wolf, defines the idea of a “moral saint” in a 1982 paper by the same name as one who is solely committed to improving the welfare of others. The moral saint’s happiness lies in the happiness of others. Instead of self-preservation, he is concerned with “other-preservation.” She writes that the moral saint

“must have and cultivate those qualities which are apt to allow him to treat others as justly and kindly as possible. He will have the standard moral virtues to a nonstandard degree. He will be patient, considerate, even-tempered, hospitable, charitable in thought, as well as deed.”

Sounds like the perfect guy, right? However, Wolf points out that the problem with the moral saint is that such extreme devotion to others means a sacrifice of his own nonmoral virtues or the underdevelopment of all the characteristics that make up “a healthy, well-rounded, richly developed character.” The moral saint would not pursue art or culture or sport for self-development, because he would be completely consumed with charitable giving or community service. There is a risk that this person would lose themselves in the service of others, something akin to the “compassion fatigue” we have seen with healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Wolf appeals to the idea that it is okay to work on oneself and prioritize wellness without guilt. In other words, one “may be perfectly wonderful without being perfectly moral.”

Peter Singer and Effective Altruism

Another modern day moral philosopher is the Australian, Peter Singer, who has no patience for compassion fatigue. He wants us to constantly acknowledge the inequality and injustice in the world and to ask ourselves if we are doing enough. Everyone knows that there are starving children in the world and refugees fleeing war, while billionaires sail around in their hundred million dollar yachts. But it is not just the billionaires he is calling out. He wants everyone with privilege to recognize that we could always be doing more. He reminds us not to be complacent in our comforts but to stretch ourselves a little further to help someone else. His philosophy spawned the movement of effective altruism, which has successfully led to hundreds of millions of dollars in charitable donations and has a new poster boy, William MacAskill, who recently published a best-selling book called What We Owe the Future and was the subject of a recent article in The New Yorker. Speaking of books, Michael Schur also wrote an introduction to Peter Singer’s book, The Life You Can Save.

Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, and Existentialism

Existentialism is grounded in the belief that existence is absurd. There is no reason that any of us are here and there is no higher power. Understandably this makes us feel anxious and fearful. Existentialism aims to give us a humanistic framework of how to act in the midst of the absurdity. Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus were 20th century French philosophers and two of the most famous advocates for existentialism. Incidentally, both were winners of the Nobel Prize in Literature. Some of Sartre’s most well-known works include No Exit, Nausea, and Being and Nothingness. Camus is famous for The Myth of Sisyphus, The Plague, and The Stranger.

While there are some nuanced differences in how each interprets existentialism, essentially they propose that there is no meaning, which frees us to make our own choices on how we define the world and our place in it. Sartre believed that “man’s destiny lies within himself.” However, this did not mean that we have free rein to do whatever we like. When we make a choice, Sartre wanted us to consider the decision as if we are making them for all people. In the face of absurdity, Camus acknowledged that the only real choice man faces in life is whether or not to commit suicide. But he encouraged revolting from the absurdity and choosing radical freedom and authenticity, which means taking full responsibility over oneself, living in solidarity with others, and maintaining deep integrity.

John Rawls and the Veil of Ignorance

John Rawls was a 20th century political philosopher and ethicist whose magnum opus was A Theory of Justice, where he explains his concept of the veil of ignorance. His thought experiment echoes Scanlon’s contractualism except that he asks us to establish the rules of society from an “original position.” This is a hypothetical place where we make decisions of how society should divide its resources before we know our roles and status — essentially from a place of initial equality. No one has any idea about what their future race, gender, orientation, income, or biological traits would be nor the family, political or socioeconomic society to which they will be born. People will know that resources are limited and they will have a basic understanding of human social life, like the importance of healthcare, education, and economic opportunity.

Rawls contends that it is from this veil of ignorance that we would make decisions that maximizes everyone’s chance of achieving happiness and opportunity, while also controlling for the role of luck in many people’s success. You might have seen people in denial of the role fortune has played, especially among the political elite when they often misattribute their success to their hard work in a “I pull myself up by my own bootstraps” kind of way instead of acknowledging “I was born on third base as a rich, white, heterosexual male.”

Harry G. Frankfurt and Bullshit

Finally, mentioned briefly in the book when Schur is elaborating on the importance of knowing how to apologize, is an amusing clarification on the word “bullshit” that has made its way into philosophy. In a 1986 essay called “On Bullshit,” the philosopher Harry G. Frankfurt distinguishes lying from bullshit. A person who lies understands that there are facts and truth, but is misrepresenting it with the intention to deliberately deceive. A person who bullshits is not interested whether something is true or false but, rather than refusing to admit ignorance, he or she continues to make assertions in order to create a perception of themselves or to achieve some effect on the listener. Frankfurt writes

“The essence of bullshit is not that it is false but that it is phony.”

Conclusion

These are some of the major and minor philosophers covered in the book and only a cursory overview at that. There are many more[3]The book mentions Thich Nhat Hanh, Joseph Overton (Overton window), Bernard Williams, among others. But there are many more like St. Thomas Aquinas, Thomas Hobbes, Friedrich Nietzsche, Bertrand … Continue reading that were mentioned (and not mentioned) that offer important insights and counterarguments. I recommend reading the book for a more nuanced exploration. If you want a deeper dive, you can read the original texts or check out the excellent Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Remember, the book is only scratching the surface and there are many more philosophers (including the religious ones) that offer significant insight into the human condition and what it means to be a good person. Whether you agree with them or not, their perspective is still worth understanding. After all, it’s the only way we can be sure that, whether we pull the lever or not, we can live confidently with our decisions.

Thank you for reading.

Interested in learning more? You can support me by:

- Purchasing How to Be Perfect or Moral Philosophy: A Reader or any of the books linked above.

- Reading my last book review: Think Again by Adam Grant

- Keeping up with my work on Instagram or Twitter

- Signing up for my mailing list below (on mobile) or the right side bar (on desktop)

References

| ↑1 | Consider morals as referring to guiding principles and ethics as specific rules, actions, or behaviors. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | As far as I am concerned, a friend automatically becomes great when he or she shares a book on how to be a better person. The fact that they were seeking their own moral self improvement is reason enough that you should keep them around. |

| ↑3 | The book mentions Thich Nhat Hanh, Joseph Overton (Overton window), Bernard Williams, among others. But there are many more like St. Thomas Aquinas, Thomas Hobbes, Friedrich Nietzsche, Bertrand Russell, and more. A great text to start with is Moral Philosophy: A Reader. |