Fourteen billion years ago, the Big Bang sprung forth, sending out matter, light, and energy, giving birth to the universe. In one of the great unsolved mysteries of physics, matter outpaced antimatter, creating something rather than nothing. And as I will explain, everything that happened after represents the ultimate and improbable sequence of events that culminated in your life.

As the universe cooled, matter came together at the right speed and energy to create subatomic particles which coalesced into atoms. Hydrogen, helium, and lithium clouds were drawn together by gravity to form our stars and galaxies.

The stars, like our Sun, underwent massive nuclear fusion reactions, combining hydrogen and helium under high pressure and temperature to create the periodic elements of our universe. As stars died and exploded, they expelled the heavier elements into space, spawning solar systems and planets.

Approximately 4.5 billion years ago, a single planet, out of the estimated 700 quintillion in the universe, formed at the exact distance and the perfect angle from its star to create the proper conditions to harbor life. The primordial soup of atomic liquids, metals, and gasses on the planet needed the correct temperature combined with the optimum energy to form the various components of Earth, from its iron core to the ozone layer.

Carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, and other atoms interacted with each other in the radioactive and charged environment to form water, carbohydrates, amino acids, nucleic acids, and lipids. Again, these organic molecules had to meet in the appropriate time and conditions to create larger, more complex compounds, in a process that took tens to hundreds of millions of years. Enzymes formed and began to catalyze chemical reactions, accelerating the transformation of Earth until larger compounds, like complex carbohydrates, proteins, RNA, and fatty acid chains, were formed.

These biological entities randomly came together until an immaculate conception led to a wholly unique entity, the first cell, which had developed the ability to reproduce itself. This is Life. As far as we know, nowhere else in the universe has this feat been accomplished. This cell learned to interact with its surroundings, sometimes using light or chemicals for energy, consuming nutrients and expelling wastes. It had to survive harsh conditions, grow if possible, and transform itself as the environment did.

Over billions of years, this cell evolved, symbiotically combining with other cells to develop higher functions. Eventually these microbes grew into multicellular organisms. Evolution was off to the very slow races. The genomes of these early beings were exchanged with other cells and mutated in a seemingly infinite number of combinations, taking divergent paths in order to create the diversity of microbiology that exists today. Some of these organisms stayed small, some grew large. The organisms divided themselves into protists and fungi, plants and animals.

The animals needed to survive a harsh environment of disease and predators. They had to evolve with the changing seasons and weather patterns. Life on Earth survived six extinction events. From fish to amphibians, from reptiles to birds and mammals, these animals struggled and thrived. After a lengthy reign, some animals, like the dinosaurs, went extinct while others, like the mammals, persisted.

The mammals grew and transformed under the push-pull influence of nature and nurture. In Earth’s lifetime, it was only recently that the family Hominidae split into Hominini and Gorillini. The former split again from our shared grandmother into the genus Pan, ancestors of chimpanzees, and Homo, the first Man. Three million years ago, the earliest humans had finally arrived.

After fighting their way into existence, Man had to survive 3,000 millenia of evolution, ego, and self-preservation. Historical evidence points towards the idea that perhaps eight or nine different species of humans existed on Earth at one time. It is also hypothesized that only one species, Homo sapiens, evolved a consciousness and intelligence that far surpassed the others. It allowed us to innovate and cooperate, forming complex social structures and inventing advanced language skills and tools. We learned to fear the “other” and it brought out our wickedness. It is theorized that anytime Homo sapiens crossed paths with another species of human, their extinction soon followed.

War and famine, illness and the state of nature threatened our existence daily. As hunters and gatherers, we roamed the savannas and forests in search of food, medicine, and community. As farmers and laborers, we learned how to harness nature for food and built permanent settlements. We manipulated the environment and used Earth’s resources to our benefit. As inventors, philosophers, and prophets we developed civilizations, cultures, and religions that developed new technologies, enriched our minds, and united the people. As explorers and adventurers, we set out into the great unknown and, despite sustaining great losses, forged paths into new frontiers.

We innovated from the Stone Age to the Iron Age, and sought to refine our existence in the time of Classical Antiquity. Depending on your perspective, the Middle Ages was a dark time (for Europeans) or an incredibly robust one (for the Islamic Empire). The Renaissance Era of the 14th to 17th centuries revived our desire to find the best of human ingenuity. Empires rose and fell. Conquerors waged far flung campaigns for their places in history, scientists risked their lives when the results of their works contradicted religion, and artists sought to explain the human condition through painting, sculpture, poetry, literature, and plays.

The Renaissance Era led us to an age of upheaval. In short order, the American Revolution, the French Revolution, and the Industrial Revolution upended the world order, bringing power and growth to new corners of the globe. Change only seemed to accelerate in the 19th and 20th centuries. As always, but perhaps never as fervently, people fought and died for freedom, civil rights, equality, and justice.

While we used technologies like the telegram, photography, radio, the telephone, and film to connect us to each other, we wielded heavy artillery, chemical warfare, machine guns, and nuclear weapons in an effort to destroy one another. The 20th century brought us the deadliest, bloodiest one-hundred years in history. Two world wars, numerous genocides, tyrannical regimes, military dictatorships, failed revolutions, multiple pandemics, and countless assassinations led to incalculable loss and grief.

Yet somehow, amidst all the unpredictability and chaos of the previous fourteen billion years of the universe, despite all of the chances that you had to not exist, somehow the genetic lineages that led to each of your parents survived and successfully reproduced. Against all odds, your mother and your father were born. And this is where it gets especially interesting.

Numerous estimations and back-of-the-napkin calculations have been attempted to illustrate the insane probability of any one of us existing. But this fun guess-timation by Dr. Ali Binazir makes this point neatly:

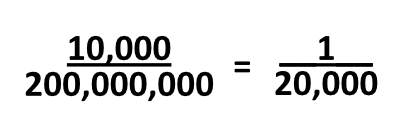

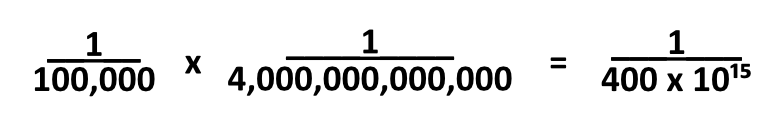

Step 1 – The probability of your mother meeting your father is 1 in 20,000. This assumes that from the age 15 to 40 your parents met one new person each day (10,000 people). Dr. Binazir also makes the assumptions that the pool of people your parents could meet was 1/10th of the world’s population 20-25 years ago (1/10th of 4 billion = 400 million) and half of that was of the opposite sex (400 million / 2 = 200 million).

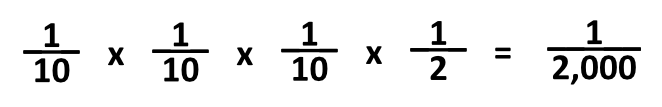

Step 2 – The probability of your mother and father getting together is 1 in 2000. Granted this is speculation, but Dr. Binazir assumes that there was a 10% chance that your parents spoke, a 10% chance that it led to another meeting, another 10% chance that a long-term relationship formed, and finally a 50% chance that it led to a child. Therefore:

Step 3 – The probability of the right sperm fertilizing the right egg is 1 in 400,000,000,000,000,000 (400 quadrillion). The average, fertile woman has about 100,000 ova. The average man will produce around 12 trillion sperm in his lifetime, which Dr. Binazir assumes only 4 trillion (33% of 12 trillion) will be relevant since they will be produced while the woman is in her reproductive years.

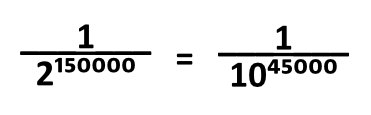

Step 4 – The probability that every one of your human ancestors reproduced successfully is 1 in 10^45,000. As I attempted to illustrate above, from the first cell in the primordial soup to your existence, there have been billions of years of an uninterrupted chain-of-life. Dr. Binazir posits that if the human lineage existed over the past three million years and each generation lasted 20 years, then there have been 150,000 human generations. He supposes that the chances of any of these generations successfully having a child that survived to reproductive age as 1 in 2. Thus:

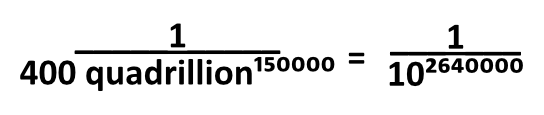

Step 5 – The probability of the right sperm and the right egg meeting for 150,000 generations is 1 in 10^2,640,000. Dr. Binazir takes the calculation one final step when he incorporates the fact that for every single generation of human that preceded us, the right sperm and the right egg had to meet (a 1 in 400 quadrillion odds) for 150,000 generations in a row.

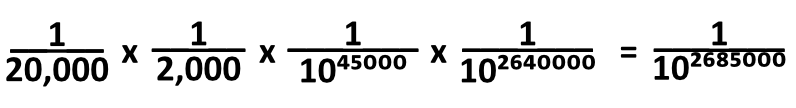

Step 6 – The probability of you being born is 1 in 10^2,685,000. To obtain the final odds, we multiply the results of Step 1 x Step 2 x Step 4 x Step 5. Just imagine the number 10 followed by 2,685,000 zeroes. For comparison sake, there are 10^27 atoms in the human body, 10^50 atoms on Earth, and 10^80 atoms in the known universe. These numbers are absurd.

Let’s pause to reflect that this calculation does not take into account the probabilities of withstanding an infinite number of close calls, unexplainable recoveries, averted disasters, lucky breaks, freak accidents, and brushes with death. Some of your ancestors experienced and survived animal bites, infections, poisonous plants, starvation, knife or gun wounds, depression or suicidal ideation, imprisonment, bomb blasts, cancer, climate change, persecution, inadvertent falls, drownings, sexual assault, physical or mental handicaps, car accidents, or other horrific misfortunes. Yet they managed to not only survive but to ensure that another generation was able to find its way into the world.

Not only does your existence defy all conceivable odds, but you come from a long line of proven survivors. You are evolution’s time-tested miracle. However, I don’t think this necessarily confers any divine meaning to our existence. And I’m sure we can all take a look at ourselves and agree that we are not without our imperfections, that nature must continue to refine its formula before we are truly “the fittest” that survive.

But it gives us reason to be grateful for our seven to eight decades of existence, however short our allotment in the universe’s fourteen billion years. It gives us a chance to create our own meaning, to not waste the moment, to work towards our dreams, and hopefully, to pass on a better world to the next generation of survivors. It is a grave and awesome responsibility. And if the task seems daunting, if the unknown future frightens you, and if the world seems like it has gone off the deep end, you can take solace in the fact that generations of your grandfathers and grandmothers thought the same thing.

Yet here you are: the definition of improbable.

Thank you for reading.

Interested in learning more? You can support me by:

- Reading my post on The Power of Compounding

- Keeping up with my work on Instagram or Twitter

- Signing up for my mailing list below (on mobile) or the right side bar (on desktop)